Emacs for Bioinformatics

GNU Emacs is likely one of the oldest pieces of software still in active development. It is also one of the most powerful systems for editing code, built by and for hackers. However, it does have a reputation for unwieldy complexity. I think this is largely undeserved. While it would take years of study to understand all its nooks and crannies, if you focus on just those features that you actually need, you can get going fairly quickly.

The purpose of this series of posts is to introduce new coders to the benefits of Emacs. I’m specifically targeting biologists, but hopefully the content will be generally useful.

You may have heard of orgmode. This is one of Emacs’ killer featues, and will feature prominently in future posts. However, for this first post we’ll stick to more straightforward features, and a simple task: developing a Bash script.

One last caveat: I work on Linux, and so the examples here will assume you are too. Most of Emacs’ features work the same on Windows and Macs, but interacting with external processes, like a Bash shell, may require additional configuration on those systems.

Objectives

- Create a new bash shell script:

- write the code

- run the code in a shell

- save the results

More importantly, by the end of this quick example, I hope you’ll see that Emacs, while a little weird, isn’t that different from more conventional programs. And if I can convince you of that, then we’ll be ready to explore some of the more useful features it has for us.

Getting Started

You’ll need to install Emacs if it isn’t already. On Ubuntu, you can do this directly from the Software Center. Other distributions will undoubtedly have it in their repositories, and you can get the latest release directly from GNU for Windows and Mac (and Linux)1.

Start by opening Emacs from the launcher, or with the command emacs on the command line. This should open up a new graphical window that looks something like this:

NB: Emacs uses a lot of keyboard shortcuts. I’ll be introducing them slowly, to keep things simple. However, it’s possible you’ll accidentally hit one, and something strange will happen. Most of the time, you can fix this by

quitting, which you can do with the keyboard shortcutC-g(that is, hold the Control key down while pressingg). It may also be helpful to know there’s anundooption in the “Edit” menu, if you accidentally change a bunch of text.

First off, we’ll create a new file: click on the “File” menu, and select “Visit New File.” You’ll see a file browser. We use the browser to create a new folder gbs-analysis, and open a new file script.sh in that folder.

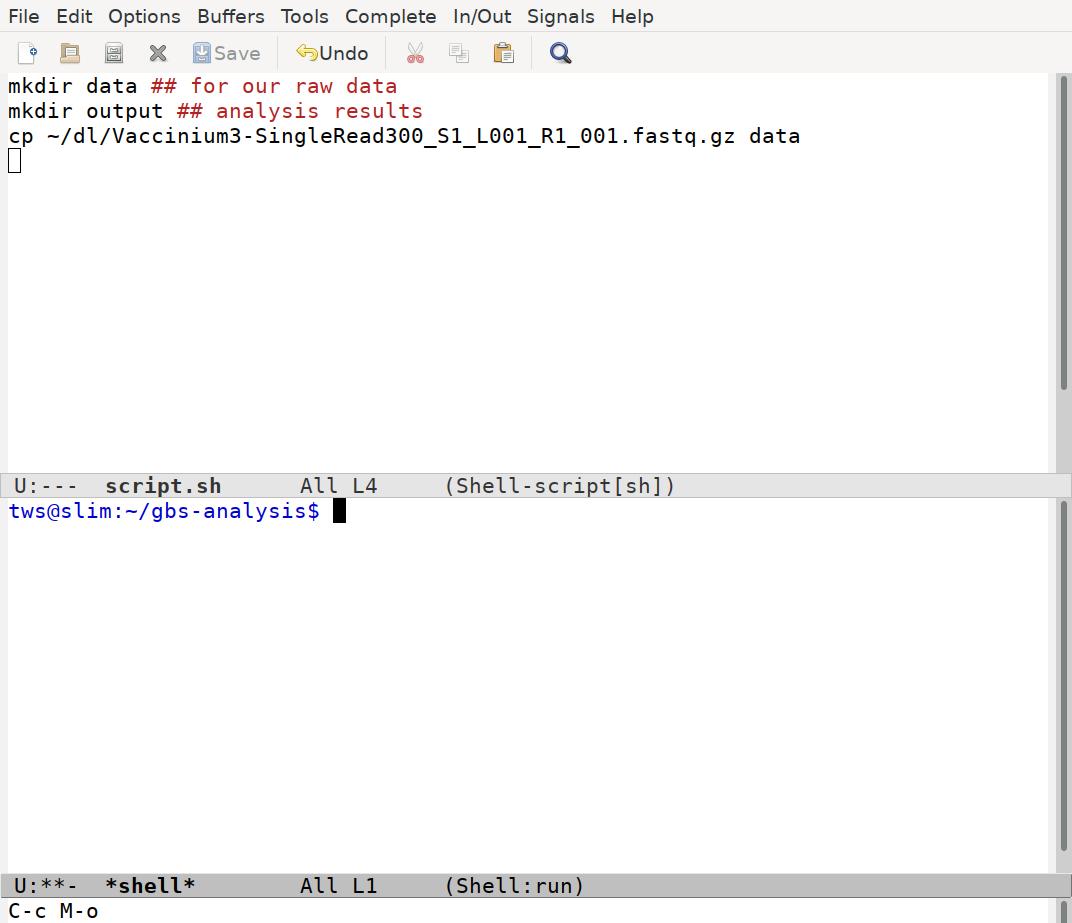

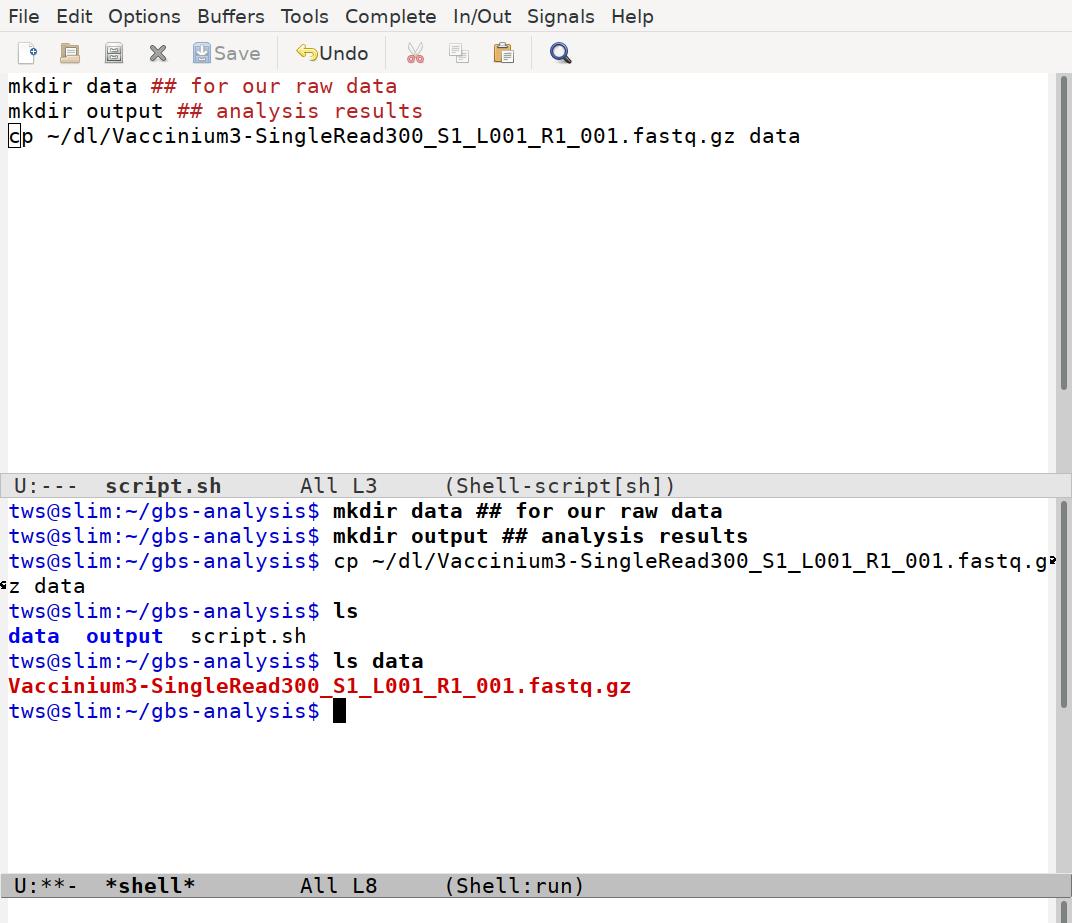

Now we have an empty file for our script. We’ll add a few commands to set up our project:

mkdir data ## for our raw data

mkdir output ## analysis results

cp ~/dl/Vaccinium3-SingleRead300_S1_L001_R1_001.fastq.gz dataTo save the file, we can use the menu “File - Save.” We’ll do this a lot, so we can use a keyboard shortcut instead: C-x C-s. That is, hold the Control key down and press x, then s.

Now we’re ready to run the code in a shell. We can start a shell from the menu: “Tools - Shell Commands - Run Shell Interactively.”

This opens a new shell terminal inside Emacs. In my case, it opens below the script window. Depending on the size and shape of your screen, it might open beside your script instead:

This terminal is almost normal: you can enter commands at the prompt and view the output, just as you would with a regular terminal. To do that, you need to move the cursor to the prompt. You can do that with your mouse. However, moving back and forth between different windows in Emacs is something that we’ll do alot, so there’s a keyboard shortcut for that too: C-x o. That moves the cursor from one window to the other. Try that a few times.

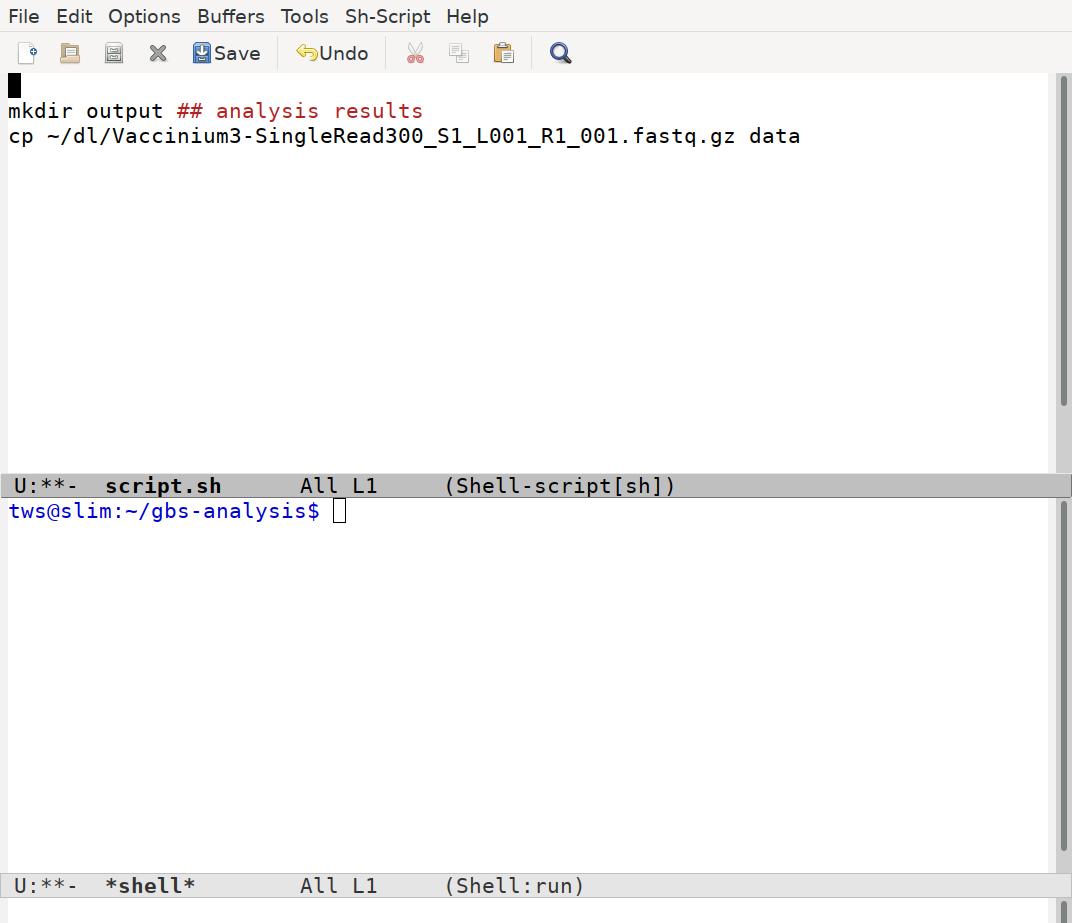

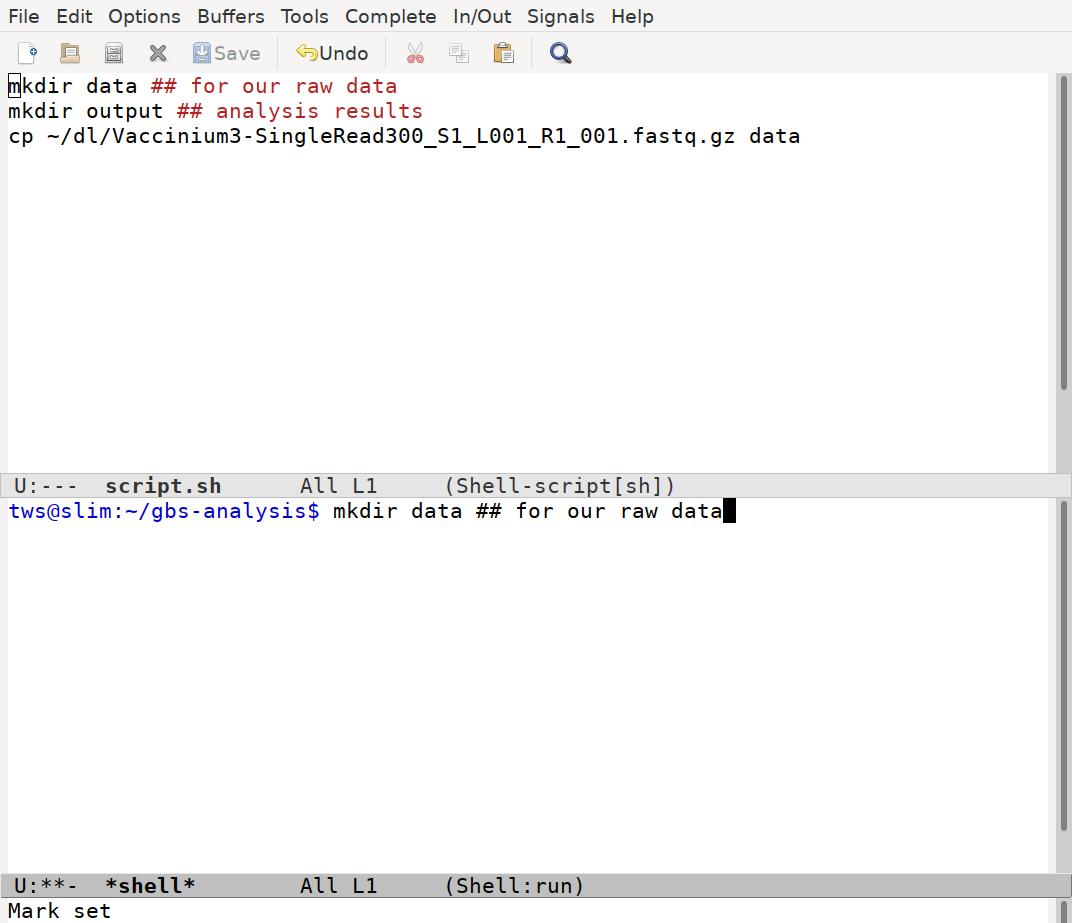

Now we have a script window, and a terminal, and we’d like to run a few lines from our script in the terminal. First, we move the cursor back to our script window (C-x o), and then move it to the beginning of the first line (you can use the arrow keys).

Here we encounter one of Emacs quirks: it doesn’t use the usual C-c/C-v copy and paste convention. Emacs was already 10 or 15 years old when this was developed, and it already had its own way: “killing” and “yanking.” We kill with C-k, and yank with C-y.

So to copy the first line, we first kill it with C-k. And it’s gone!

We can get it back by “yanking” it with C-y. Now we’re back where we started, except that the contents of the line are stored in the “kill-ring.” Now switch back to the shell prompt and yank again:

Now the line we killed is on the command prompt and ready to run. Hit enter and we’ll create our new directory. Repeat with the next line. The third line won’t work of course, because you don’t have the same file on your computer, but I’ll use it here to round out my example.

We can enter commands directly in the terminal. I’ll use ls to check that the new files and directories are all where we put them:

Remember I said the terminal is ‘almost’ normal. One of the things that’s not normal about it is that you can move around in it with the arrow keys, and kill and yank text if you like. You can even enter additional text in the transcript if you like. That might be useful if you want annotate something; just be careful not to hit enter when you do this, or the text will get entered at the prompt, which you usually don’t want to do.

You can also save the text in the terminal window as a text file, again using the File - Save dialoag, or the keyboard shortcut C-x C-s. That’s not very useful for this toy example. But if you had spent hours on a bioinformatic pipeline, you could then save a record of everything you’d done as a text file.

So… what?

That may have been a little underwhelming, if you’ve ever listened to an Emacs zealot ramble on about how mind-blowing this program is. What I hope you got from this short introduction is:

- Emacs has some quirks, but it’s basically just a text editor that you can use like any other editor, with a few concessions

- Having your script file and terminal in the same program is handy for developing scripts

There are some obvious deficiencies here:

- transfering text from the script to the shell is a bit clunky

- maintaining a script file and a separate file with the shell output will get confusing quickly

It would be much better if we could:

- write our script in a single file

- have the commands sent automatically to the shell

- have the results pasted back into the script file at the appropriate location

That would be a big improvement. Emacs can do that and more:

- mix different languages, including Bash, R, Python and more in one file

- include human language, including sections, formatting (bold, italics), and links to other files and websites – all in the same source file

That’s where orgmode comes in, and it really is a killer feature. But before we get there, we need to get a bit more familiar with the basics of Emacs. For this, I strongly recommend the built-in tutorial. You can start it with C-h t from Emacs. It takes 20 or 30 minutes, and explains the basics of getting around in the program. Try that out, and we’ll look at orgmode in the next post.

There are several customized Emacs distributions that provide improved default settings. Some of them are quite good, but I’m going to stick to standard Emacs to minimize distractions.↩︎