Ryan Byrne Smith, 30 November 1975 – 7 July 2020

We came here, to this arena, three days ago. It was overwhelming, such a huge, empty space. We’re a small family. And we’re so, so much smaller without Byrne. I thought we’d made a mistake.

It felt like I’d watched a star burn out. A star that shone over me my whole life was gone, and no one noticed. No one even knew it was gone.

Ed told us not to worry. People were coming, and they would fill this room for Byrne. And here you are. You saw him. You noticed. You knew what he was, and what we have lost. What all of us have lost. And that means everything to me, and my parents and my family. Thank you.

We live in Ottawa, and I only see Byrne a few times a year. We saw him last week, for the first time since the lockdown. I understand he’d been getting a lot of attention with his covid haircut. If you were wondering what that would have looked like in another six months, you’re looking at it.

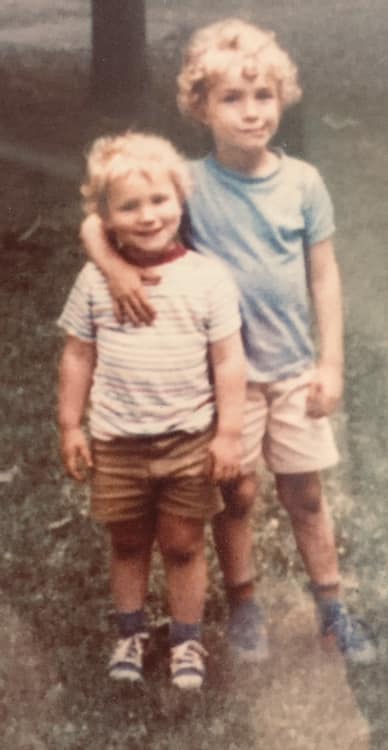

People often comment on how much we look like each other. I like that. I especially liked it when people said I looked like Byrne’s younger brother. I like that we had this physical connection, even if it wasn’t easy for me to talk about it. I was so proud of my brother Byrne, and so proud to be his brother. I like to think, if I look like him, even a little, then maybe I can be like him.

Many of you will know that Byrne ran for office, as a member of the Green Party. I saw that campaign. I also saw his first campaign. It was for student council, vice president I think, at Lakeport Highschool. I was in the bleachers with the rest of the school. Byrne was on stage, waiting with the other candidates, for his turn to speak.

When his time came, he stood up, walked right past the podium, past the microphone, and jumped right off the stage. He didn’t need amplification, he came to preach. “I have a dream!” he hollered. He wailed, storming up and down the gymnasium as he did.

He was fearless. And he was ridiculous. And so beautiful.

And he was our vice president that year.

Those of you that have been fortunate enough to have a meal at Byrne’s house, you know he was a man who loved food, and even more, he loved to cook. Smoking turky for 12, 14, 16 hours before Christmas dinner. Making the best Americanos with his super-fancy espresso machine. He made his own doughnuts in middle school. When we lived in New Zealand, he learned to make Pavlova.

Even before he could cook his own food, he knew what he liked. Mome always got us chocolate advent calendars for Christmas. One year, after I was in school, so Byrne would have been 3 or 4, mom came upstairs and went to check up on him. The calendars were in their places, on the mantel above the fireplace. And Byrne was in his place, right underneath. He couldn’t reach the mantel from the floor, sohe jumped. And he made it!

But he couldn’t pull himself up. And he couldn’t touch the floor either. So he was stuck, just hanging there.

I won’t go on, but that’s not even his only advent-calendar caper. He was tenacious.

We all suffer. It’s the same for everyone, and everyone’s suffering is unique. And so for Byrne. He has had his share, and more, of struggle. But he persevered. He picked himself up, more than once, and built himself a life that he loved. And we loved seeing him live it.

I want to thank his brothers and sisters at the firehall. Your community has given him so much. He has received so much joy from his time with you. It’s a blessing.

He hasn’t been with corrections as long, but working with his team there has also been good for him. I think he really enjoyed being part of your team, and working together with you.

But it’s more than that. Byrne was a social worker. He spent a lot of time, and gave a lot of love, to the kids in his homes. He was incredibly empathetic, and the passion he brought to his work was inspiring.

He was a fundamentally decent and caring person. His personal struggles softened his view of the people around him. And his training and experience gave him the tools to help people, and especially the people who most needed help.

He came to visit us in Ottawa last year. We met a friend of mine, a professor, who works with inmates and studies the justice system. It was striking for me. This was my brother, who I know and love, and he’s everything he always was: funny, charming, and larger than life. But as I listened to them talk, I saw the other side of him, his professional self. Insightful, articulate, with a deep understanding of difficult issues: mental health, addiction, welfare and the legal system.

They made plans. Byrne was going to come back to speak to the class. That was something I was looking forward to seeing.

Byrne was extraordinarily compassionate, and he’d found a way to direct that compassion in a way that would really help people. Now that he’s gone, it’s going to be up to us, everyone here, to do a little bit more, to carry some of the weight that Byrne had shouldered.

We won’t be doing this alone. Neither was Byrne. He had you, his friends and colleagues. He had me, and my parents. Their support never waivered, even if it wasn’t always clear how to help him. They were there.

And he had Christina. It’s hard to understand how two people can be so perfect for each other. Laurel and I, and my parents, we talked about this a lot. About how happy Byrne was with Christina. Her love and support was absolute. Which wasn’t to say Byrne got a free pass. When he needed a push, or a kick, he got one. But he also got so much love, love that he returned.

I am so grateful that he had you, Christina. He deserved every bit of the happiness you shared together. And you never deserved to lose him like this.

If there was anything we could do to make this better, we would. But there isn’t. All we can do is support each other, and we will.

It will be the hardest thing we’ll ever have to do. But look at all these people. They’re here for you.

And we’re all here for Byrne. Rest easy my brother. I love you, and you’ll always be in my heart.