Bakeapple flower, 12 June 2024.

In a few short weeks the AAFC bakeapple team will be back in Makkovik to start another summer of bakeapple research, alongside Inuit Food Systems Research Technician Marilyn Faulkner, and guides Barry Andersen and Todd Broomfield. While the berries are still several months away, June is an important time in the life of an appik.

Bakeapples form flower buds in late summer, tucked away underground and out of sight. They mature slowly over the winter. When the ground starts to warm up in the spring, they’re ready to poke their heads up at last and grow towards the sun.

Bakeapple emergence, May-June 2024. Marilyn Faulkner/AAFC.

When the flowers open, we’ll finally learn something they’ve known since the buds formed last year: whether they’re a boy or a girl! Most other plants have male and female reproductive structures together in the same flower (such as redberries and blueberries), or in some cases in different flowers on the same plant (such as spruce and alders). Bakeapples have separate male and female plants, and all the flowers on a plant will be the same sex.

That might sound strange, because bakeapples only have one flower on a stem. But what we don’t see above ground is that each of those tiny stems is attached to an underground rhizome (a horizontal stem just beneath the surface), and that rhizome can spread for ten meters or more. Which means that each individual bakeapple stem is just one branch on an underground bakeapple “tree”.

Bakeapple rhizome

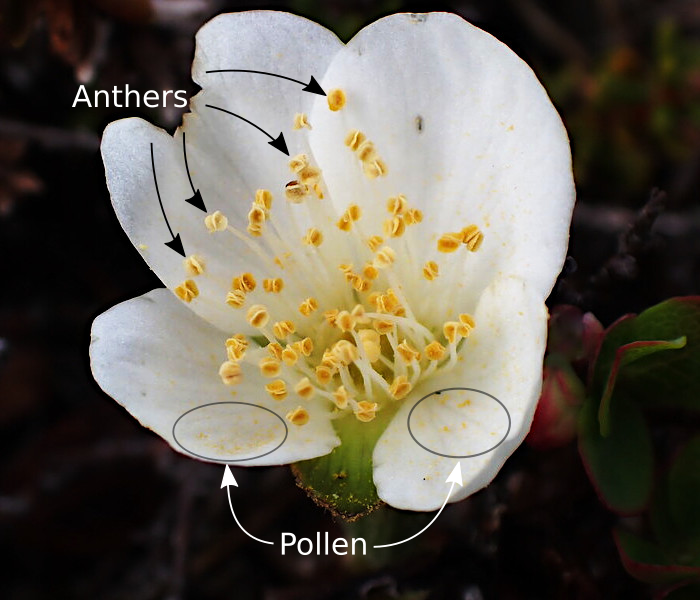

Male bakeapple flowers emerge first, a day or two before the females open. They also stick around a little longer after the females have finished flowering. We recognize male flowers by the ring of stamens just inside the petals, each one topped with a yellow anther. Male flowers attract insects with a combination of sweet nectar at the center of the flower; and pollen, released from the anthers. As the flies travel from flower to flower, they transfer (hopefully!) some of the pollen to female flowers, enabling them to start developing fruits.

Male bakeapple flower. Some of the pollen grains have fallen out of the anthers, visible as a yellow powder on the white petals.

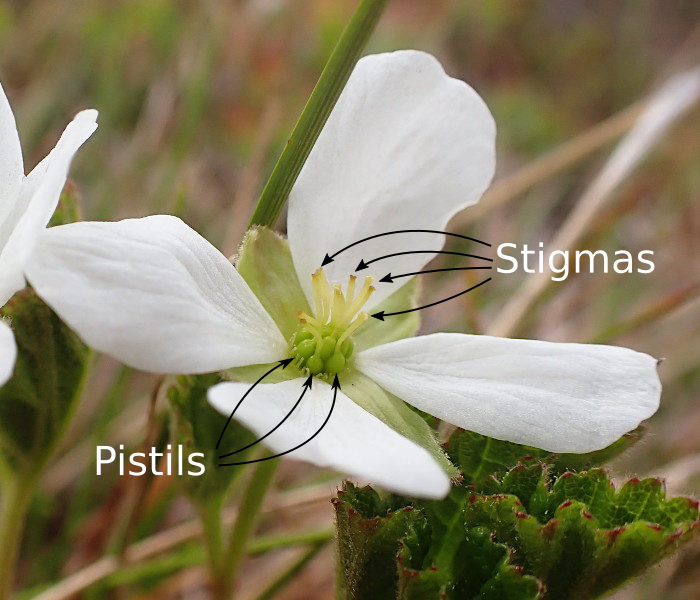

Female bakeapple flower. There is a cluster of green pistils in the center of the flower, each topped with a fuzzy stigma that collects pollen off visiting insects.

Female bakeapple flowers also have stamens, but they don’t develop fully or produce anthers. Instead, they have a cluster of green pistils in the center of the flower. The pistil contains the reproductive parts of the female flower. At the top is the stigma, which scrapes pollen grains off the bodies of visiting flies. When that happens, the pollen grain will germinate, travel down the tube-like style, and fertilize the ovule (egg) at the base. The fertilized ovule will then release hormones that tell the plant it’s ready to make a fruit. If all goes well, 4-6 weeks later we’ll have a delicious appik to pick.

Pollinators on male bakeapple flowers. Left: A syrphid fly. Right: An Empidid fly. The flies will use their mouth parts to lap up nectar from the bottom of the flower. They need to climb through the anthers to do so; in the process, pollen grains will get stuck to their bodies.

If the flowers bloom too early, or there is a late cold snap, they may be damaged or destroyed by frost. Bakeapple plants are very cold-hardy, but their flowers are tender.

Frost-damaged female bakeapple flower: note the blackened pistils.

When the weather cooperates, and the flies do their job as pollinators, the fertilized bakeapple starts developing a fruit. The first signs are the white petals dropping, and then the green sepals close up around the ovaries. This provides a safe space for the fruit to ripen.

A female bakeapple: pollinated by a fly, dropping its petals and closing up the sepals around the developing fruit.

2025 will be our fourth year studying Makkovik bakeapples. We will contintue collecting a variety of data on different aspects of bakeapple biology. All of the methods we use are safe for bakeapples and for people, and do not interfere with any harvesting. Here are some of the methods we use to study bakeapples, and the equipment you might see around Makkovik this summer:

- Flower tagging: we use metal tags to mark individual plants. This allows us to count how many flowers survive to produce fruit each year.

A bakeapple plant with a labeled copper tag loosely looped around the base of the plant.

- Flower transects: we have set stakes to mark out 10 meter transects (straight lines) that we return to each year. We’ll count all the male and female flowers on the transect, including how many of the females have been damaged by frost or insects. When we return in August we’ll count again, to see how many fruits were produced along each transect.

Erica and Charlie Mae counting bakeapples along a transect.

- Time-lapse cameras: we have a set of (mostly) weather-proof cameras that we focus on freshly opened flowers. They are set to take a photo every 10 minutes during the flowering season, and then every hour until the fruit ripens. This gives us more information about the timing of flowering, and how long it takes for a berry to ripen.

One of our weatherized timelapse cameras, pointed at a bakeapple flower (just above the left side of the camera).

- Temperature loggers: at each of our transects we have air and soil temperature loggers. We’ll use the data from these instruments to better understand how temperature influences when the flowers emerge, how long it takes to produce a fruit, and how extreme heat and cold impact the plants. At least, that’s what we’re planning to do. We’ve had some challenges with this equipment. The foxes take great delight in digging them up and chewing them to pieces!

Temperature loggers. Left: An air temperature logger. We’ve started replacing this older model with a new version that doesn’t have exposed wires. The foxes love to chew on those wires! Right: a soil logger. These instruments are buried 6 inches under ground, marked with flagging tape. The flagging tape is very interesting to foxes, though, so we’ve stopped using it.

- DNA sampling: we’ve collected leaf samples from some of the sites, and plan to complete the rest of the sites this year. We extract DNA from the leaf samples, and do a kind of “fingerprint” analysis. This allows us to determine how many individual plants are present at each site, and how closely they are related to each other.

A leaf tissue sample. We put the leaves in a bag of silica gel crystals in order to dry them out quickly.

- Flower netting: new this year, we will be putting mesh bags on a few of the bakeapple flowers. This will prevent insects from pollinating those flowers, so we can better understand how the plants respond to pollination.

A pollination bag, here being used on a tomato.

- Nutrient sampling: also new this year, we will be collecting leaf and soil samples, in order to better understand how the sites differ in terms of soil quality, and to identify which nutrients the plants may be lacking.

We’re glad to answer any questions about our work. Please feel free to chat with us in person, say hello while we’re working on the boardwalk/Makkovik Hill/Ranger Bight, or get in touch by email. It’s a privilege to be working in Makkovik and we are grateful to everyone for your kind interest and support.